“The superb pianist Han Chen draws on an equal affinity with Romantic and contemporary repertoire to bring us a survey of Ligeti’s Études which stands among the best.” (Gramophone)

“Han Chen’s execution of formidable polyrhythms and hairpin transitions are uniformly excellent… a sterling document of the Ligeti Etudes.” (Sequenza21)

“A powerfully persuasive reading of music that makes a good introduction to Ligeti.” (AllMusic)

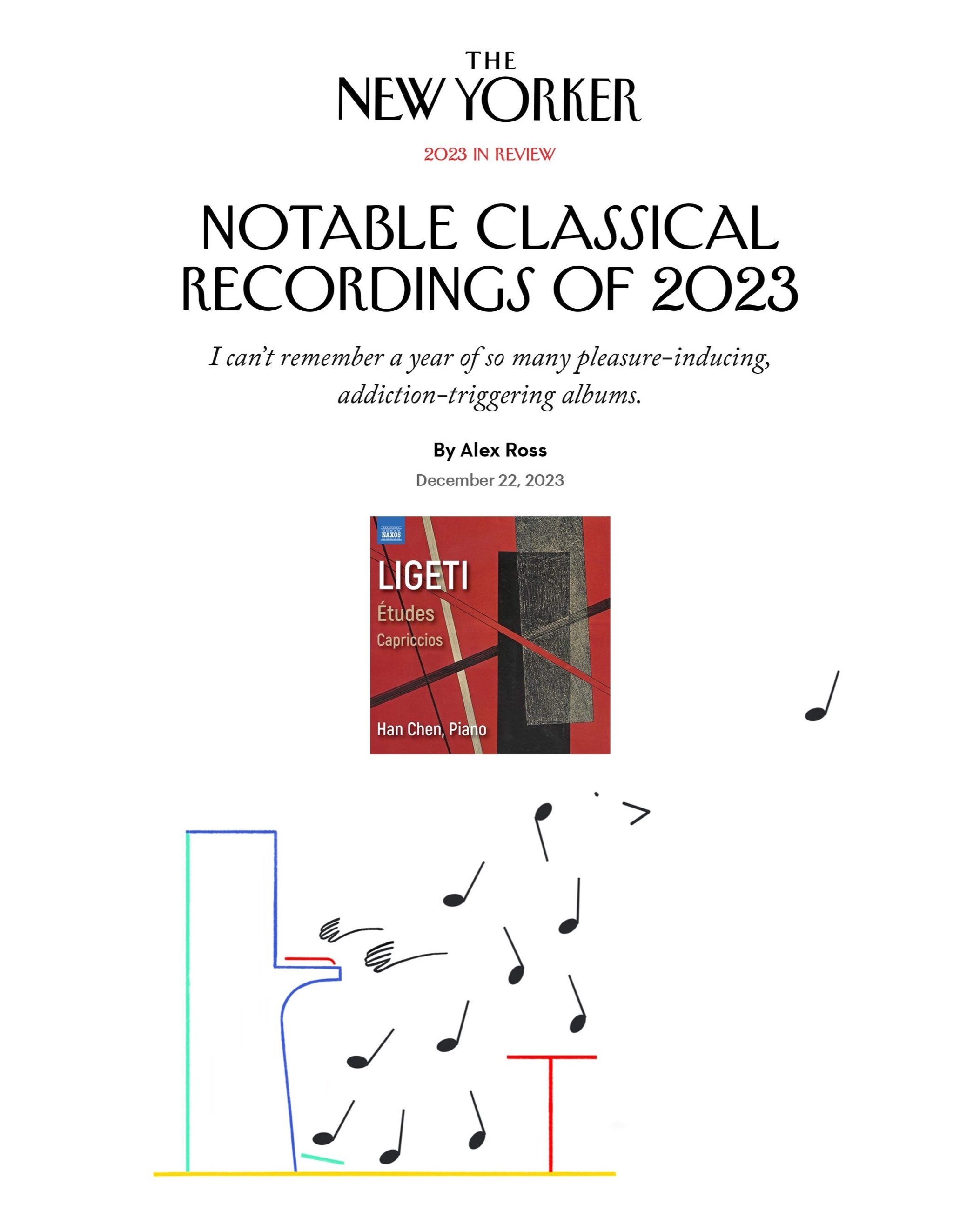

Released May 26, 2023 on Naxos Records

György Ligeti’s Études redefined the piano’s tonal possibilities and are considered one of his major creative achievements, as well as being one of the most significant sets of piano studies of the 20th century. They inevitably draw on influences from the past such as Chopin and Debussy, but avoid any sense of eclecticism.

Ligeti’s often spectacularly virtuoso use of complex rhythms and geometric patterns proceeds from simple core ideas to create music that is ‘neither “avant-garde” nor “traditional”, neither tonal nor atonal’, and always backed by that glint of humour in the composer’s eye.

Recent Press

Behind the Scenes

-

Book 1

1 No. 1. Désordre (Molto vivace, vigoroso,molto ritmico): this rapidly evolving study with its polyrhythmic velocity moves upwards and, ultimately, almost off the top of the keyboard.

2 No. 2. Cordes à vide (Andantino con moto, molto tenero): chord sequences of a Satie-like simplicity become more complex, as the prevailing rhythm gradually folds in on itself.

3 No. 3. Touches bloquées (Presto possibile, sempre molto ritmico): two primary rhythmic patterns gradually interlock with distinctly, as well as distinctively, Bartókian results.

4 No. 4. Fanfares (Vivacissimo molto ritmico, con allegria e slancio): a further polyrhythmic study, in which the melody and its accompaniment frequently and deftly exchange roles.

5 No. 5. Arc-en-ciel (Andante con eleganza, with swing): the most overtly Debussian of these studies, not least with its rising and falling in arcs that aptly evoke the rainbow of the title.

6 No. 6. Automne à Varsovie (Presto cantabile, molto ritmico e flessibile): always transforming its initial descending idea, this mirrors the first study by finishing at the bottom of the keyboard.

Book 2

13 No. 7. Galamb Borong (Vivacissimo luminoso, legato possibile): these subtly shifting rhythmic patterns readily evoke the sound of the gamelan, hence the ‘nonsensical Javanese’ of the title.

14 No. 8. Fém (Vivace risoluto, con vigore): after the Hungarian for ‘metal’, this tensile study in rhythmic continuity has a poetic coda in which the underlying harmonic pattern is laid bare.

15 No. 9. Vertige (Prestissimo sempre molto legato): the harmonic and spatial distance which is opened-up between the two hands soon becomes one of demonstrably ‘sheer’ proportions.

16 No. 10. Der Zauberlehrling (Prestissimo, staccatissimo, leggierissimo): entitled ‘The Sorcerer’s Apprentice’, this centres on a lightly-tripping melodic line kept in perpetual rhythmic motion.

17 No. 11. En Suspens (Andante con moto): in absolute contrast, this highly elegant study creates an amorphous web of harmony constantly on the verge of a tonalsounding resolution.

18 No. 12. Entrelacs (Vivacissimo molto ritmico, sempre legato, con delicatezza): a gentle crossing of rhythmic patterns, increasing in dynamics as they traverse the keyboard from right to left.

19 No. 13. L’escalier du diable (Presto legato ma leggiero): ‘The Devil’s Ladder’, a driving toccata which zigzags its way across the keyboard then on to a climactic peal of bells near the close.

20 No. 14. Columna infinită (Presto possibile, tempestoso con fuoco): after the Constantin Brâncuşi sculpture, harmony and rhythm fusing into a dense sonic column rising-up the keyboard. The more complex first version,

21 No. 14a. Coloana fără sfârşit (‘Column without End’), follows as an encore.

Book 3

7 No. 15. White on White (Andante con tenerezza): a study (almost) entirely on the white notes, it unfolds in placidly canonic textures before suddenly assuming greater velocity near its centre.

8 No. 16. Pour Irina (Andante con espressione, rubato, molto legato): for pianist Irina Kataeva, it unfolds calmly but increases in motion with shorter note-lengths and more complex textures.

9 No. 17. À bout de souffle (Presto con bravura): its ‘Out of Breath’ title indicates the headlong two-part texture of this study, which culminates unexpectedly in a placid sequence of chords.

10 No. 18. Canon (Vivace poco rubato – Prestissimo): This short yet eventful piece proceeds as exchanges between the hands, fast and then hectic, before it concludes with a tranquil coda.

-

Hungarian composer György Ligeti was born in the Transylvanian town of Dicsőszentmárton (now Tîrnăveni in Romania) on 28 May 1923. The Second World War saw the murder of his father and brother in concentration camps, and his own close encounter with death on the Eastern front. Despite such upheavals, he graduated from Cluj Conservatoire, and began studies at the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest in 1945, teaching theory, harmony and counterpoint from 1949. He soon began to evolve an idiom combining folk music with more experimental means, as in Six Bagatelles for wind quintet (1953) and the First String Quartet (1954), though such pieces could hardly have secured performance in a Hungary subject to Stalinist dictates.

In December 1956, while the Soviet militia suppressed the Hungarian Uprising, he escaped to Austria, heading to Cologne where he found work at the studio of West German Radio. Although he produced an electronic masterpiece in Artikulation (1958) the circumscribed manner of post-war serialism held little appeal for one having experienced ‘closed systems’ at first hand and his first orchestral piece, Apparitions (1959), caused consternation with its pivoting between the earnest and the inane. His 1960s music traversed distinct lines: on the one hand the not necessarily humorous Poème symphonique (1962) for 100 metronomes or Aventures et Nouvelles Aventures (completed in 1965), wordless music theatre more ominous than hilarious; on the other, the orchestral piece Atmosphères (1961) and organ work Volumina (1962) whose exquisite textural contrasts characterise such works as the Requiem (1965).

Ligeti moved forward by gradually reintegrating the past according to his own needs. Hence the harmonic translucence of Lontano (1967) was followed by the reintroduction of melody in Melodien (1971) then the interplay of melodic lines in San Francisco Polyphony (1973–74). He also composed such overtly abstract works as the Second String Quartet (1968) with its playful counterpart in the Chamber Concerto (1970), and the never literal repetition of Clocks and Clouds (1973) confirmed an interest in American minimalism heard to startling effect in Three Pieces for Two Pianos (1976). The culmination of this period was the surrealist opera Le Grand Macabre, which received its premiere in Stockholm during April 1978.

Ligeti then sought a way out of the serial impasse that avoided a return to classically-based tonality. The Horn Trio (1982) was criticised for its Brahmsian soundworld, but its overtly Hungarian inflection and recourse to different tunings informed the music from his last two decades. Running across these are the piano Études which redefined the instrument’s tonal possibilities, along with a large-scale Sonata for Solo Viola (1991–94) and concertos for piano (1988), violin (1993) and horn (1999). While he had long contemplated a second opera, initially on Shakespeare’s The Tempest then Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Ligeti wrote no further compositions after 2001. He died in Vienna on 12 June 2006.

As Ligeti himself describes it, the impetus for ‘… composing highly virtuosic piano études … was, above all, my own inadequate piano technique.’ Piano music is prominent in his output prior to his escape to the West in 1956, notably Musica ricercata (1953) or the Due capricci which were written in 1947 while studying with Sándor Veress. The first piece (Allegretto capriccioso) unfolds across three continuous sections, the Bachian intricacy of its figuration enhanced by keen modal inflections. The second piece (Allegro robusto) is more impetuous, drawing on the Bulgarian manner as found in Bartók for its harmonic and rhythmic content.

Almost no solo piano music emerged during Ligeti’s involvement with the European avant-garde. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, he rethought almost every aspect of his aesthetic, resulting in music which might be described as ‘post-tonal’ in its creative and unprejudiced approach to the Classical tradition. Among the first fruits of this reassessment was Book 1 of the piano Études, finished in 1985. A second book emerged during 1988–94, with a third book started in 1995 but left incomplete after Ligeti had ceased composing.

Numerous influences are at work throughout these pieces. The epochal collections of Chopin and Debussy are both an inevitable presence, as are the keyboard techniques of Scarlatti and Schumann. Yet the role of sub- Saharan African culture (particularly as regards its collective approach to drumming) is no less crucial in terms of the complex rhythmic polyphony here utilised; indeed, polyrhythms and shifting pulses are essential both to the sound and feel of this music. Geometric patterns, especially the self-repetition of ‘fractals’, are a vital stimulus – as were the rhythmic and metric innovations of the maverick American composer Conlon Nancarrow (1912– 1997) and the pianism of totemic jazz figures such as Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans. That said, there is never any sense of eclecticism within the actual music: to quote the composer once again, ‘… it is neither “avant-garde” nor “traditional”, neither tonal nor atonal. These are … études in the pianistic and compositional sense. They proceed from a very simple core idea and lead from simplicity to great complexity: they behave like growing organisms.’

The Études are playable complete, as three books, in various selections or as individual items.

-

Recorded at Oktaven Audio, Mount Vernon, New York, USA

Producer, engineer and editor: Ryan Streber

Assistant engineer and editor: Edwin Huet

Piano technician: Dan Jessie

Booklet notes: Richard Whitehouse

Publisher: Schott Music

Cover: Untitled from Constructions: Kestner Portfolio 6 by László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946)